The rubato story, Chopin – Nocturne in E minor.

When depicting the musician as the artist who plays with passion and expression, tempo rubato is an important issue. And a difficult one for sure. Because , in its very essence, it can only be an individual, personal way of playing. Which makes it difficult to judge.

Describing rubato as a way of playing where one deviates from the basic tempo makes it almost sound like playing wrongly, not keeping the tempo. But then that’s what it actually is: to free yourself from the strictly metronomic tempo, slow down or accelerate a bit or even insert a small pause.

So, why then is a pianist praised for playing such a beautiful rubato? And why are we appalled when someone plays “far too much rubato”?

What does rubato do with the music? Why do we do it?

In my opinion it’s simply a way of telling the story. Compare it with giving a speech or a lecture: you want to take people by the hand and guide them to the word or sentence that you think the most important to convey. How do you do that? You can of course use dynamics, raise your voice or whisper. But you may also regulate the speed at which you arrive at the point you want to make. Speed up to get attention or slow down to rise expectations. Or hold your breath for just a second before “le moment supreme”.

The latter makes me think of one of Arthur Schnabel’s famous quotes: “The notes I handle no better than many pianists. But the pauses between the notes – ah, that is where the art resides.”

Though tempo rubato is not exclusively used in music from the Romantic Period it seemed obvious to me to record something from Chopin:

Nocturne in E minor, opus 72 nr. 1. The opus number was given posthumously, it is actually his first Nocturne, written in Poland before his moving to Paris. Listen to the young Chopin:

When rubato is about telling a story, it’s about your way of telling the (composers) story. Seducing the audience to join you.

After thoroughly studying the composer’s sheet music and practicing it , listening to recordings, after doing research into more aspects of the piece: historical context, relation to other compositions etc. When you feel really prepared you tell your version of the story. The way you understand it, the way you hear it inside. Which doesn’t mean that one can not learn tempo rubato from teachers or other pianists, on the contrary: a good role model can help you to find and shape your sense of timing.

There are musicians and critics who disapprove of this personal touch of the performer, who want only the written text to be presented “as it is”.

To me that’s simply not possible, gradations may differ but we all have an inner guide or clock which sets our pace as we play a piece. Call it a congenital tempo rubato 😉 . Or simply character.

It’s something you may come across when playing together with another musician. When both of you play “right” (i.e. not-wrong) but still your sense of timing is different, you don’t breathe together. Which makes it hard to tell the story. Over time, when playing together many, many times your playing “locks” with the other. You walk together.

Also as a listener it may take some time to “get the story” , and not only regarding tempo rubato. When I first heard Teodor Currentzis with his musicAeterna orchestra performing Mozart’s Requiem in Salzburg (!) it sounded very strange to my ears. Tempi, accents, phrasing , not to mention his use of dynamics in short motives: all different than what I was used to. But very expressive, so it made me curious. When I re-listened a couple of times I eventually got “in sync” with his performance, started to love the intensity.

Check him out anyway, this a bit controversial but highly interesting young conductor with both a vision ánd a mission.

PS

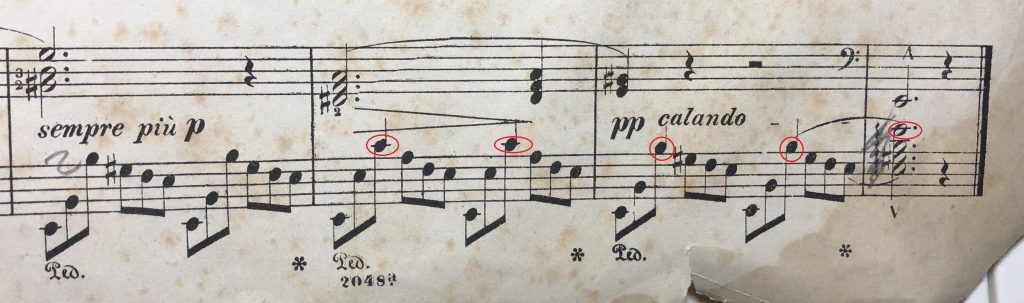

Listening to my recording maybe you were surprised a little hearing a rather prominent inner-voice at the ending. As pointed out in my Welcome blog these are “one take” homemade recordings with sometimes unintentional accents and even mistakes but this one wasn’t:

It is written in the score of my old book with Nocturnes, see the red circled crotchets in the left hand triplets. I couldn’t find this inner-voice in other editions I studied so I’m not sure about the “authenticity” but rather liked it, so played it 🙂 .

- As usual I invite you to post your comments to this blog article so we all benefit from each others views and insights. That’s my main objective here so please share your thoughts!

- Note: to enhance interaction the comment section has been revised: the green bell underneath your comment means you’ll be notified by email when there’s a reply posted to your comment. On top you can also subscribe to receive notifications for all posted comments and reply’s.

- Did you spot the “big wrong note” in my recording?

Another nice piece of music- a showcase of why Chopin is amongst the greatest composers for piano. Rubato indeed. No Chopin without it. Actually, I tend to say that one should not play Chopin without a Rubato-approach. His music seemd to beg for it. Next to the rubato, Paul, you also play around with dynamics. Call it a second rubato-approach in one piece. And again one that needs to be there. No Chopin without it. There is one point though, I am still thinking off. Have not made my mind up. Rubato is the step up to a full-personalised style… Read more »

I can see your point there August but I’m afraid I don’t have the answer. Where is the point where a performer drifts of too far from the written composition? Here we also touch the subject of the balance of power between composer and performer. Not only regarding playing rubato. Below, in another comment, Clemens suggests that composers who perform there own work often improvise (to some extent). Which would mean that we should not be tethered too much to the written music. But then, also respect the written music. Pfff, this gets hard…. As Clemens is both pianist and… Read more »

*For translation see below*. Interessant onderwerp Paul en je bevestigt zelf al in het bovenstaande dat geniale muziek op meerdere manieren uitgevoerd kan worden en daarbij overeind blijft staan. Wat toch ook wel vaak vergeten wordt is dat vele klassieke componisten fantastische improvisators waren en je ook bij Chopin en zeker bij zijn loopjes uitgeschreven improvisaties hoort die zo goed zijn dat ze onderdeel van de compositie worden. Naar mijn bescheiden mening werden deze werken dan ook met behoorlijke vrijheid zeker door de componisten zelf uitgevoerd. *Interesting topic Paul and you already confirm yourself in the above that genius music… Read more »

I think you’re right. Did you read John Mortensen’s article Signs of Life, Piano Journal Epta, december 2019? It’s about how improvisation disappeared from the classical performance. “all the great composers in history were excellent improvisers and yet it is a dead art among almost all classical performers today”. If not, I’ll send you a copy:-). But playing rubato is not about the art of improvisation but about playing “free” with respect to the written notes It’s also about what I call “the balance of power between composer and performer”. I’m in a discussion with August about that in another… Read more »

Playing in bands your story made me think of these magic moments of “synchronized rubato” or, more common, “groove” !

Hi Peter, I think rubato (flexibility in tempo) itself is not often an instrument of expression in popmusic because the rhythm section in fact has to be “strak”, tight in tempo. Don’t you think so? Maybe sometimes in a ballad with only guitar or piano accompaniment. But as to the moments of bandmembers syncing together, “grooving”: Yes, these are absolutely magical moments. Four hearts beating as one?.

I like it, tempo rubato..and apply to classical play. .. own story ..

Very colorful and personal playing of a piece of music that was unknown to me.

I’ll take that as a compliment, thank you.